The Architecture of Utopia

UMOCA - Assemblage Process Grant

Nick Pedersen / Amy Macintyre (Iris House)

“The gardener digs in another time, without past or future, beginning or end.. As you walk in the garden you pass into this time -

the moment of entering can never be remembered.” - Jarman, Modern Nature

Synopsis

An experimental and collaborative visual art installation featuring large-scale printed work and plantings incorporated into a public garden setting. Referencing historical allegories of the garden, and ideas of world-building that harken back to a mythical past or yearn for a future utopia. Inspired by my collaborator’s and my experience of restoring our own quarter-acre garden plot over the past eight years.

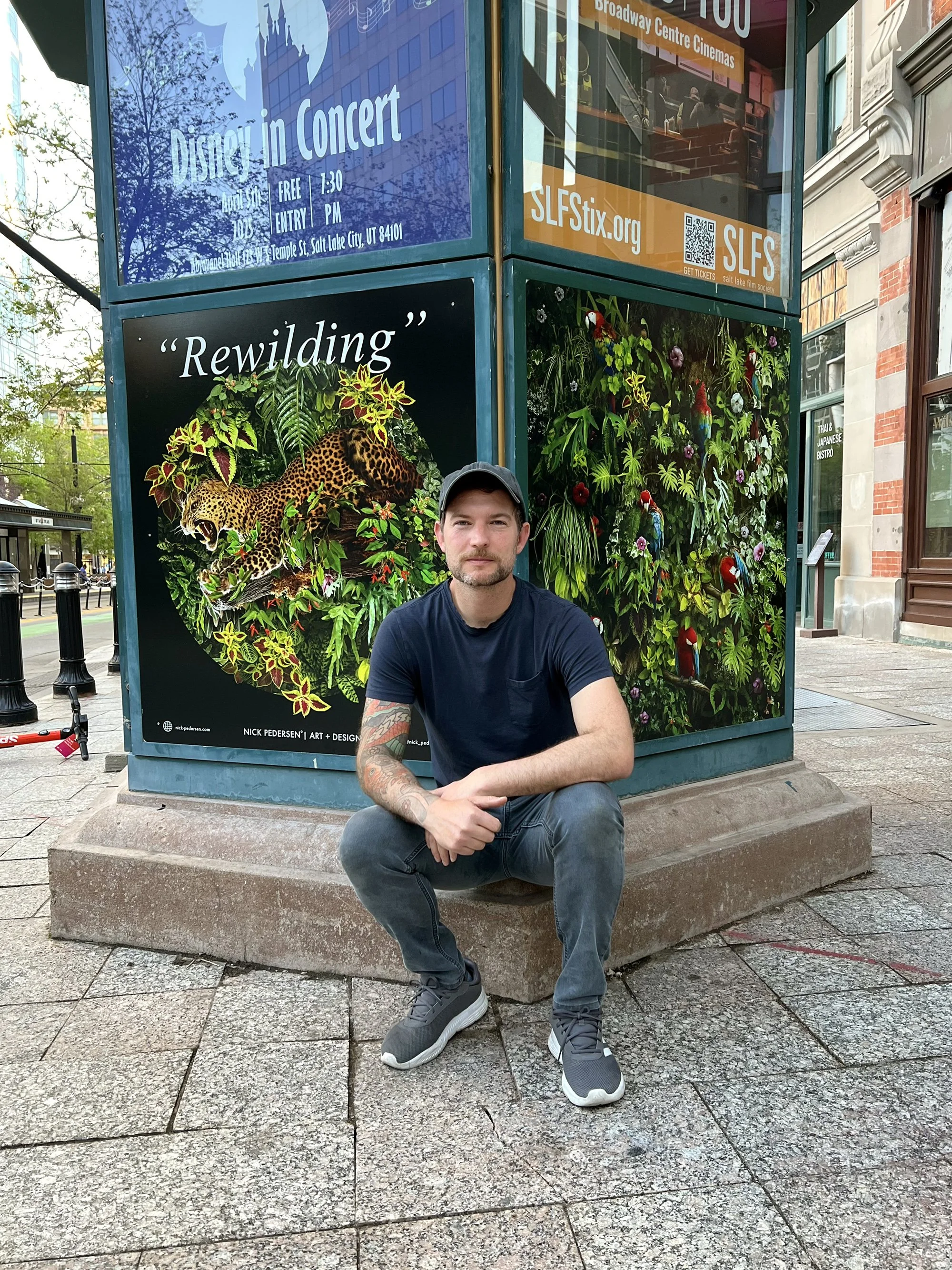

"Rewilding" - Erosion Gallery

"Slow Apocalypse" - UMOCA

Introduction

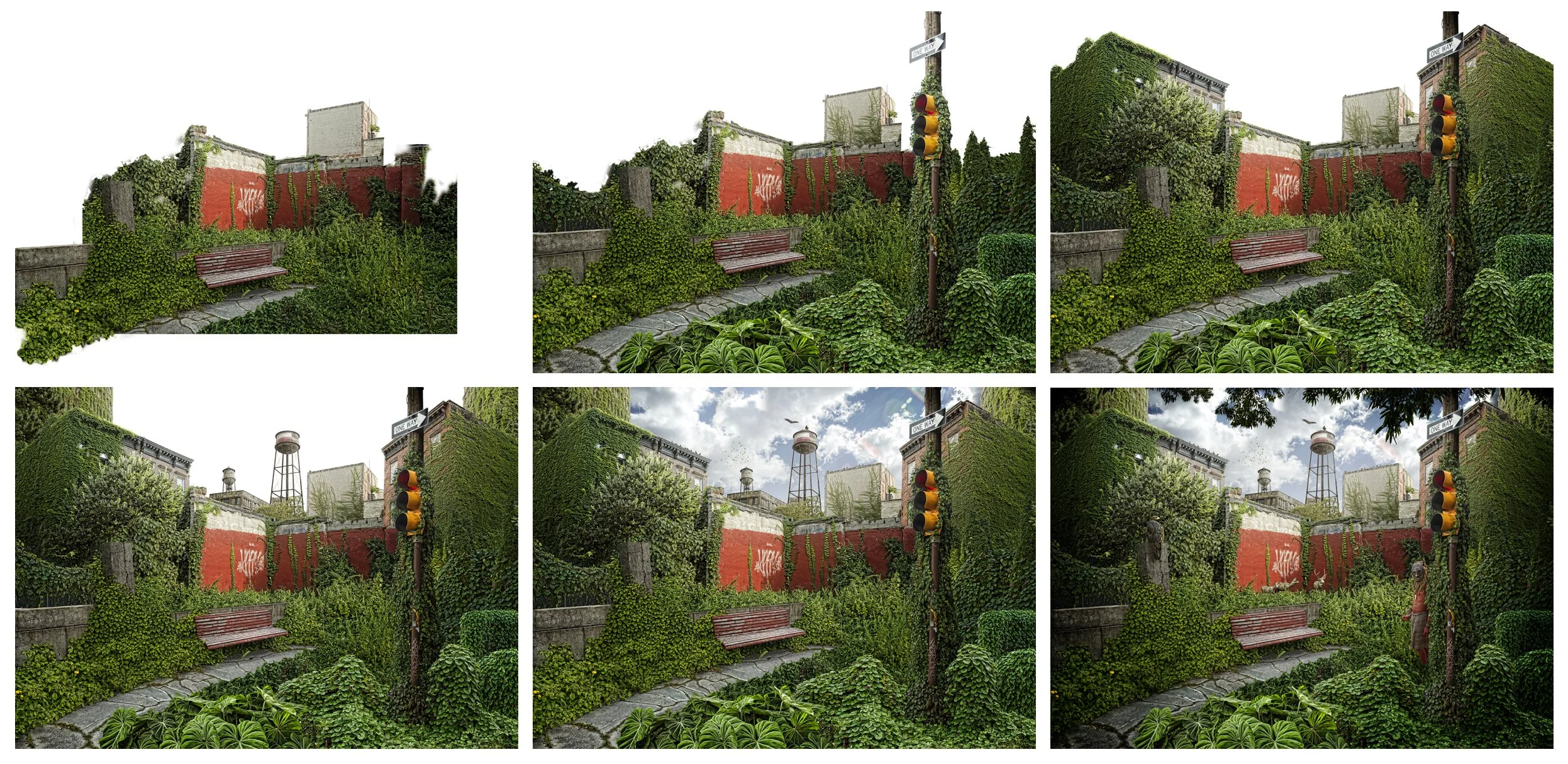

As a photographer and digital artist, much of my past work has explored environmental issues of the Anthropocene, an age of human impact on the natural world. From climate change and more extreme weather events to loss of habitat, biodiversity, and species extinctions, our planet is quickly approaching a strange and unpredictable future. In response, my artwork plays off of older forms of beauty in art making, referencing sublime landscape paintings, animal studies and still lifes, fanciful wallpaper, and textiles. My images appropriate these picturesque styles and idealized nature imagery to create elaborate juxtapositions with subversive elements from modern civilization. A main theme recurring in my work is beautiful decay, creating large-scale pieces that focus on concepts like the reclamation of nature and rewilding the modern world.

“Sanctuary”

"Vanitas" - series

Much of the photographic source material that I use in my work has come from our own garden that my partner/collaborator Amy Macintyre and I have been restoring over the past eight years. In that time we have transformed our quarter-acre plot that was once dried out grass and weeds into a thriving habitat with a wide diversity of low-water plants. As a master gardener and landscape designer, Amy planned the layout of different sections of the garden, and we’ve now planted more than twenty trees on our property, as well as dozens of shrubs, numerous perennials, and a vegetable garden. We have watched our garden grow throughout the seasons and it has become a personal sanctuary and food source for us, as well as an established ecosystem and wildlife haven for birds, animals, and insects.

Overview

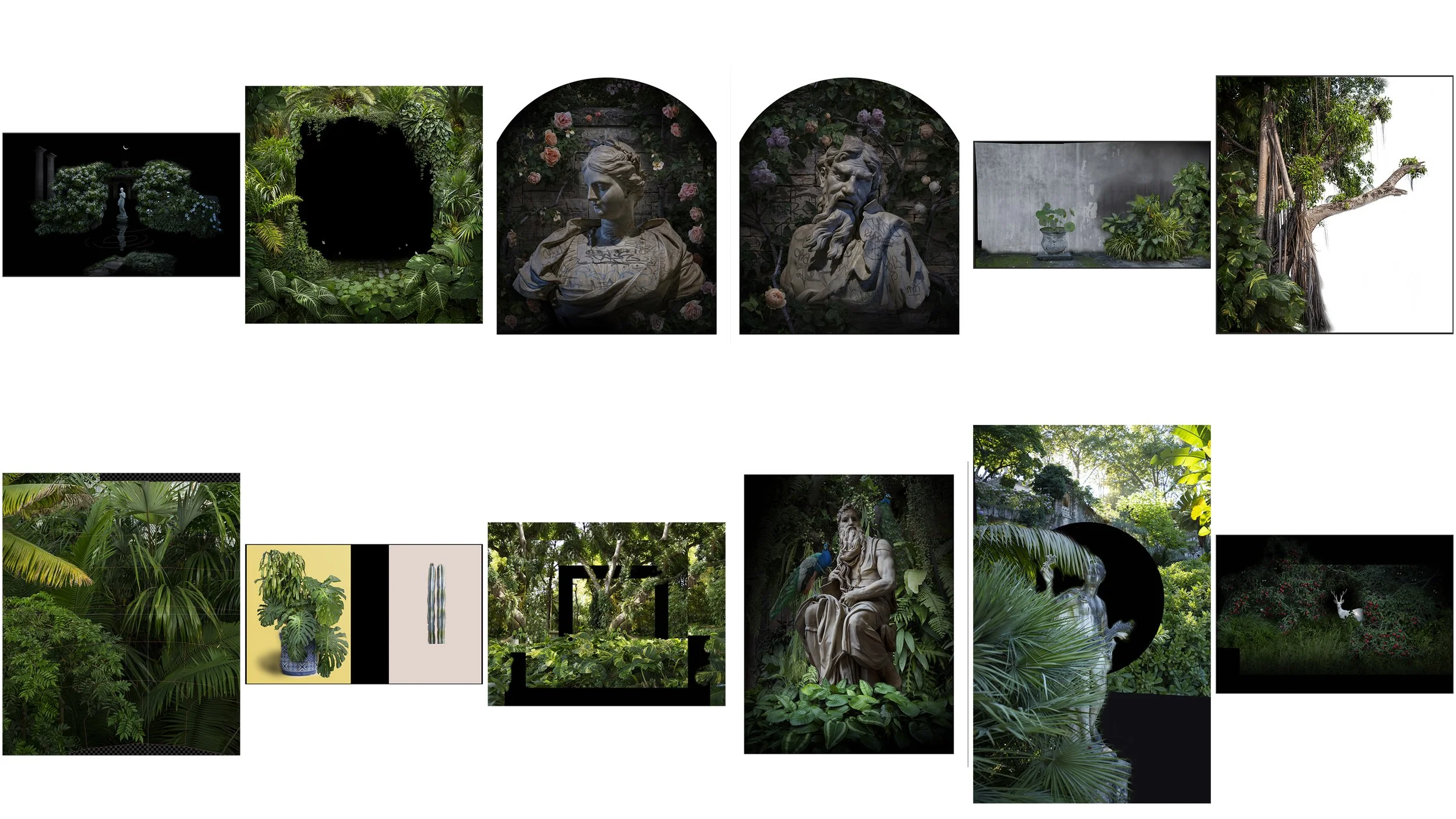

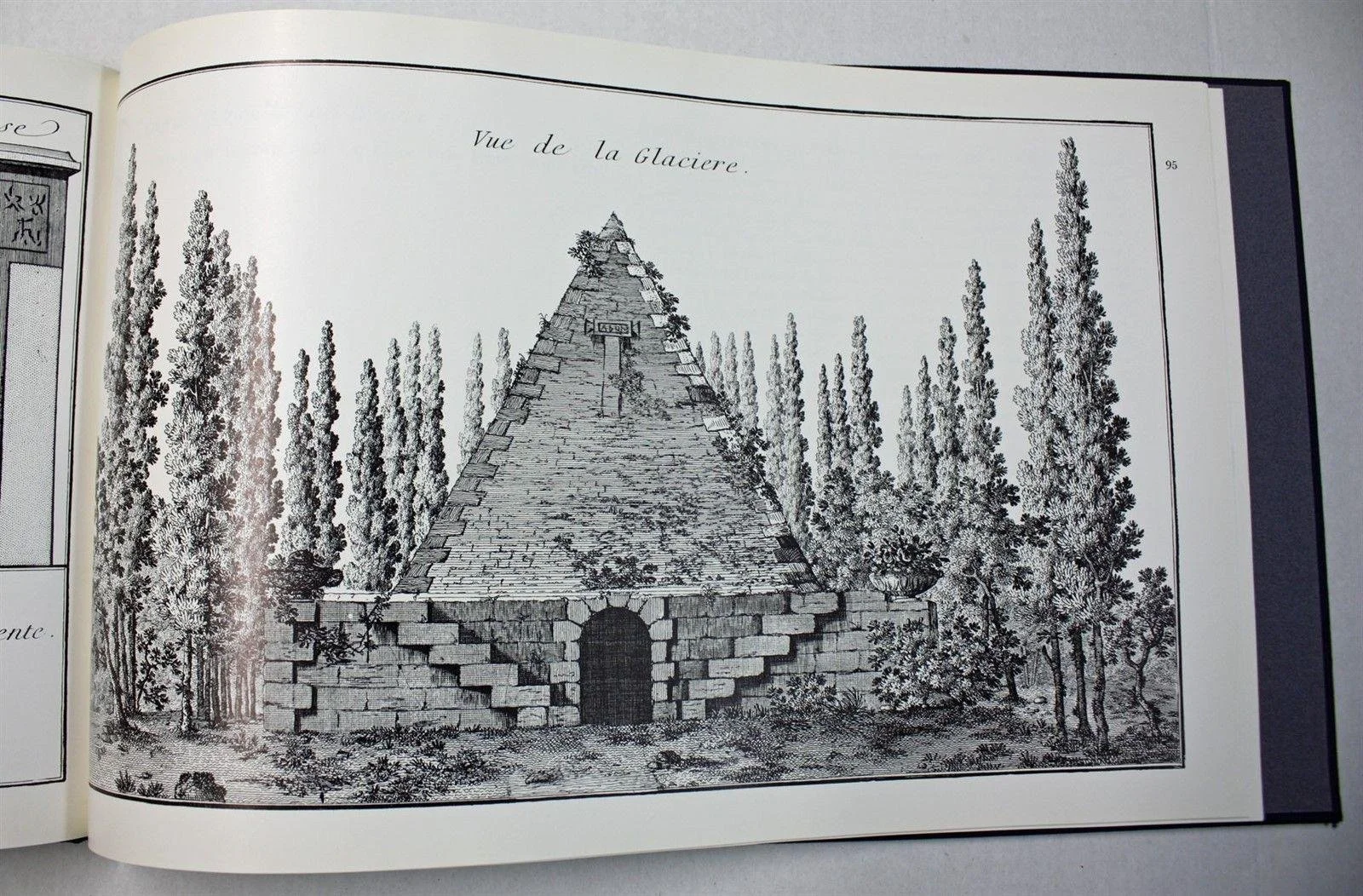

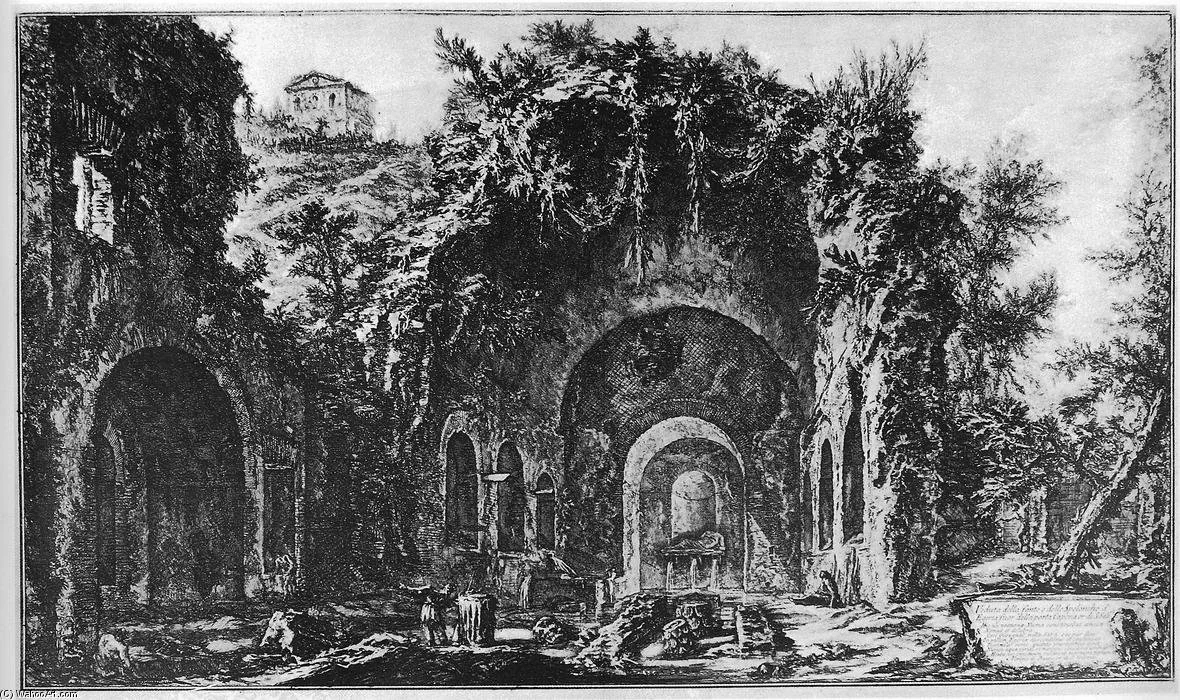

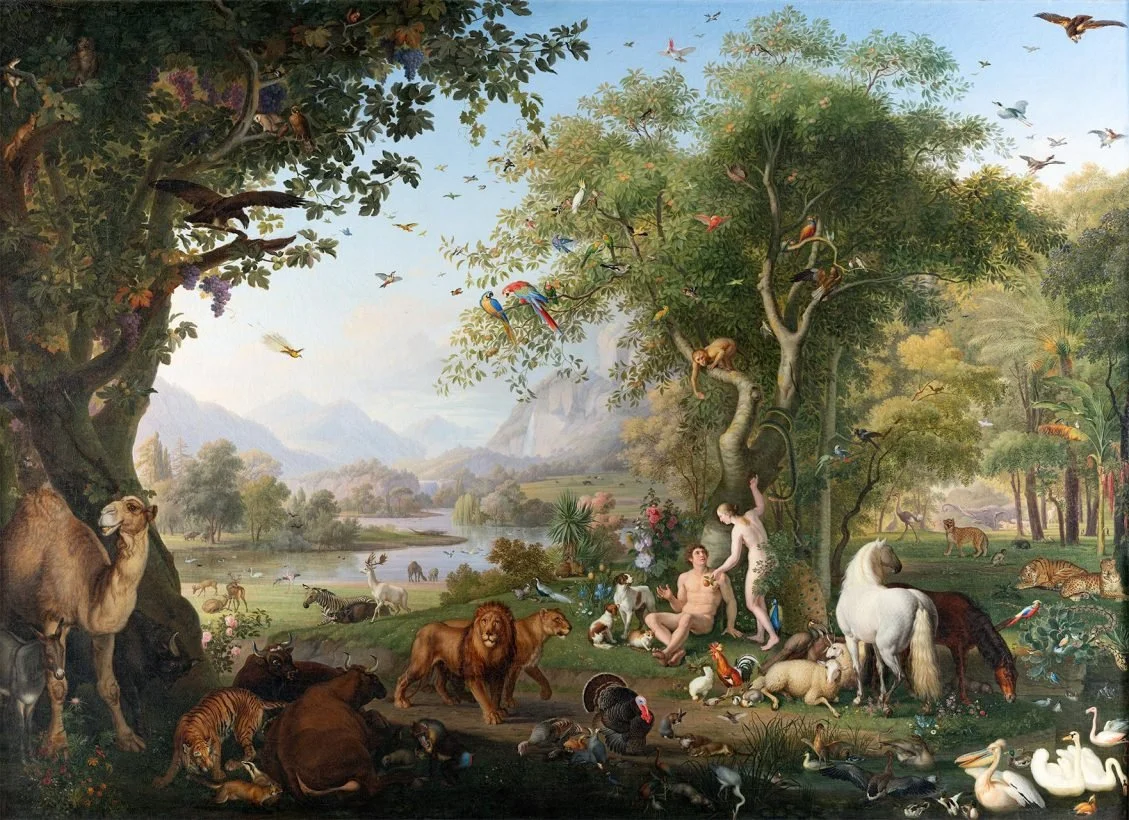

Our project proposal is titled “The Architecture of Utopia”, referring to the historical symbolism of the garden as an opening onto visions of paradise, inspired by Arcadian concepts and edenic myths surrounding this romanticism of the sublime. We are specifically interested in exploring concepts from the Victorian era, where the garden was allegorically set in the realm of thought. Many gardeners of the time created spaces for reflection on the human condition, through picturesque landscapes, plantings, and statuary that were to be contemplated for meaning. They were enamored with the emotion of melancholy, seeing the garden as a mirror of society, and many of these gardens had such emblematic titles like the Temple of Ancient Virtue, Elysian Fields, and the Valley of Life and Death. To create theatrical spaces around these themes, many Victorian gardens incorporated elements known as ‘follies’ where they built structures or ruins from other times and places meant to serve a place of repose. These included mystical temples, pyramids and obelisks, rockeries and statues, grottoes of nymphaea, and other philosophical references from history and myth.

References

“What attracts one to ruins is their incompleteness, their instant declaration of loss which we can complete in our own imaginations, enquiring into

the causes of a broken world.. Ruins invite the mind to complete their fragments.” - Cluitmans, On the Necessity of Gardening

The main idea behind this era of the garden was a contemplation of time and mortality, such as the prevalent concept of Vanitas, reflecting on the transient nature of earthly desires and beauty. Through gardening, you experience this cyclical nature of time that flows with the seasons. In our own garden we enter this space, every year seeing these perpetual cycles of growth and decay, life and death, chaos and order in the world that we have planted. To the Victorians, the pleasure garden was both a refuge from the world, and a place to examine the symbolism of nature and antiquity related to contemporary life. As writer and gardener Olivia Laing writes in her book In Search of a Common Paradise, “A garden as a time-capsule, as well as a portal out of time.” We are very interested in this allegorical dichotomy of the garden as a ‘portal’ into the timeless, as well as a ‘mirror’ reflecting on the time we live in.

References

“Feral Age”

For our Assemblage process grant, we are proposing a collaborative investigation into these utopian concepts of world-building through art and nature, and ideas of the garden as a symbolic space of continuous creation, destruction, and rebirth. In essence, we want to reference these Victorian ideals of picturesque beauty and philosophical allegory, but reframe them in a contemporary sense. In much of my past work I have created scenes like this that are both beautiful and unsettling, envisioning ruins from modern civilization in contrast with a futuristic ecological utopia. With this project, we are interested in combining these concepts and visually focusing on the garden not only as a conceptual subject, but also as the physical setting for a public art piece. Mainly, our idea is to experiment with creating or depicting a ‘folly’ in this contemporary landscape, using the garden as a space to contemplate modern humanity and our connection to the natural world.

"Void"

"Darkness"

Project

During my artist residency at UMOCA, I worked on many concepts combining nature and allegory, to create an installation focusing on themes like the reclamation of wilderness and rewilding the modern world. Much of this work played off of older forms of beauty in art making, referencing sublime landscape paintings, animal studies and still lifes, fanciful wallpaper, and textiles. This Assemblage grant proposal represents a continuation of these ideas, as well as the beginning of a new direction of experimenting and creating work with my collaborator and partner Amy Macintyre. Alongside creating our garden projects, we have long dreamed of starting a collaborative that would incorporate our interests of art and gardening. Our goal is to combine our efforts to create larger public art garden projects and visual art installations in the future. Inspired by the hardy and prolific irises that were the only plant thriving in the driest conditions in our yard when we first moved here, we’ve chosen ‘Iris House’ as the name of our collaboration together.

"Slow Apocalypse"

"Remnants of Time"

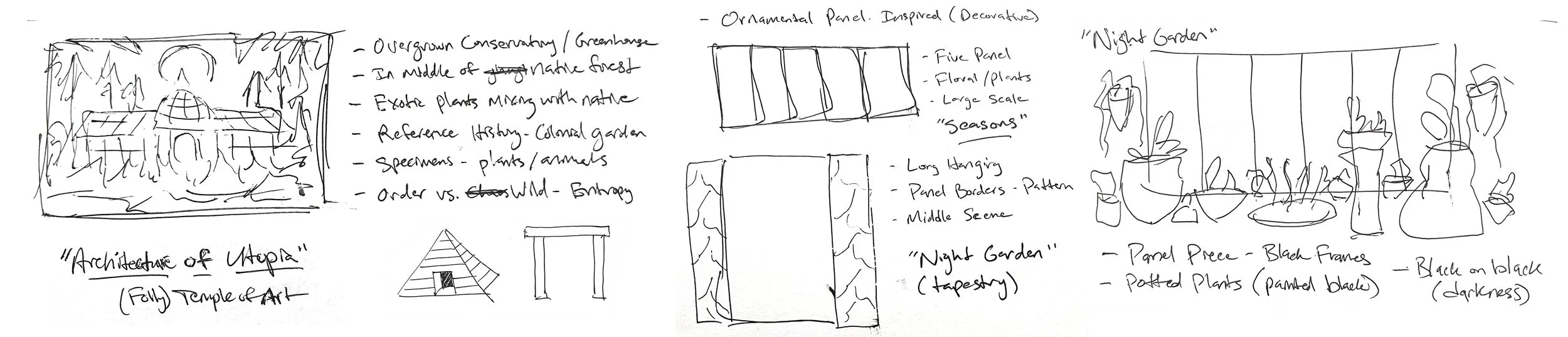

Concepts

The main concept for our project will be an experimental and collaborative visual art installation featuring large-scale printed work and plantings incorporated into a public garden setting. Here are a few examples of conceptual directions as a starting framework.

Temple - “Architecture of Utopia” - Physical structure to display artwork as a series of large screens, surrounded by plantings or potted plants.

Portals - “Psychic Garden” - Artwork embedded into the garden, as portals leading to another space or mirrors reflecting back - images within images.

Theater - “Theatre of Plants” - Maximalist installation of garden inspired imagery and plants, with overlaid projections and a sound installation.

Ruins - “Garden of Tranquility” - Artwork depicting contemporary ruins as ‘follies’ in the garden surrounded by plantings and installed in existing spaces.

Seasons - “Passage” - Series of large printed screens depicting each of the four seasons and accompanying plants with different bloom times.

Art Reference

Mockup Test

Sketch Ideas

Engagement

To engage with the public, our project is inspired by the Victorian ideal of creating the garden as a meditative and theatrical space. In this way the viewer becomes a collaborator of meaning, encountering artistic scenes that are to be read and interpreted. The installation would be integrated into a garden setting and we are researching and connecting with local spaces like Red Butte Garden, Allen Park, The Garden Store, Gilgal Gardens, and the International Peace Gardens to see what is possible. The final result would be a pop-up exhibition with an opening event, as well as a public lecture at UMOCA about our process of making connections through gardening, art, and environmentalism. I have much experience in creating art exhibitions, planning large-scale projects, and presenting my work to the community. Recently, I completed a year-long public art project through a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropy and the Salt Lake Arts Council, to design a series of billboards raising awareness about the decline of the Great Salt Lake. We’re very excited about this opportunity to work on another public art grant that would engage with a new audience from an unexpected location like the garden.

UMOCA Artist Talk

"DoomScrolls" - AIGA Show

Wake the Great Salt Lake

Context

Throughout history the garden has represented an earthly paradise, from Arcadian myths to the Garden of Eden. Our state of Utah also has this mythology as a promised land that was chosen by the Mormon pioneers, proclaiming from the biblical verse “the desert shall rejoice, and blossom as the rose”. But what does it mean to grow a garden in the desert? There is a deep history in the West of colonization and control, attempting to make the land into the idealized image that we desired. Much of this involved establishing a separation from the wilderness over time, such as contemporary examples of golf courses and green lawns that are being watered during historic drought conditions. We are interested in this contradiction between this idealization of nature and the realities of environmental issues like climate change and habitat loss. I think many contemporary artists are investigating concepts in this genre of new naturalism, and creating work that speak to these ideas of romanticism and fabrication.

References

In Victorian times, there was a widespread garden mania where exotic plant species from around the world were highly sought after, and a single rare tulip bulb from Asia could cost as much as an entire house. Known as Tulipmania, it was a highly speculative time and actually ended up crashing the Dutch stock market. During times of financial uncertainty, and other disruptive issues like war, famine, and disease, gardening is thought to be a human instinct. A good example are the victory gardens created by the public during WWII that became an independent food source and the allotment garden movement established more green spaces in this industrial era. In a similar way, during the Covid years there was a huge plant craze influenced by social media and apocalyptic thinking of the world coming to an end. That was also when we began throwing ourselves into gardening, as something to ground us and keep our sanity. It was a refuge, and we spent much time creating outdoor spaces to inhabit, surrounded by the many different varieties of plants, trees, and flowers we cared for. In this way, I think gardening becomes an antidote to dystopia because it gives you the opportunity to create a new world.

Research

We are very inspired by the work of renowned garden designer Piet Oudolf, who created the High Line in New York, and his vision of designing beautiful spaces as well as a thriving ecology. He focuses on a more natural approach to gardens, planting large drifts of native meadow plants, flowers, and grasses that attract birds and pollinators. This concept of wilderness gardening, creating spaces that are more a part of our environment has been a major focus, and over the years our yard has transformed into an entire ecosystem. I think this motivation of conservation and sustainability in an era of aridification and drought is the main connection between the themes in my artwork and building our garden.

“All gardeners are stewards of the biosphere.” - Laing, The Garden Against Time

Before

After

Timeline

The timeline for this project would consist of four main parts, starting with experimentation and planning for the first few months to working on the project through the end of the year. The next steps would be creating the physical pieces and assembling organic elements of the project and then installing them at the location. Finally, the project would culminate with an opening event and a public arts lecture.

Process

1. Experimentation / Planning

Since this is an experimental process grant, the first part of our time would be spent testing out ideas conceptually and visually to see how the collaboration will unfold. This includes capturing new photographic source material of garden and plants, combined with other elements to create the visual impact that I am looking for in this body of work. It would also include planning landscape design concepts and creating digital mockups to visualize how the project would look in a physical space.

Photography - Source Material

Example of Digital Collage Process

2. Working on Project

The next phase of the project would be production, starting with creating the complex digital collage imagery used to create my work. Then I would print the large-scale pieces in my studio using my digital printer to create the series of panels, screens, and other printed work. We would also be finalizing ideas for incorporating plants in and around the installation, whether it’s working in existing garden beds or curating a series of pots and planters, or flower arrangements. This would include planting bulbs that would grow in the spring/summer, starting seeds in our greenhouse, and transplanting plants from our yard that would work for the installation. We would also begin organizing material and constructing the physical displays for the artwork to be installed in a garden landscape.

Studio

Recent Image Tests

3. Installing Project

Once we have a location selected we would make plans to install the artwork pieces, along with setting up and caring for the plant and garden elements. We really like these spaces where our art installation and planting concepts would blend seamlessly into the landscape, or could even help beautify and bring attention to some parks that are a bit more neglected. Here are the five possible garden locations that we have researched and are making connections to collaborate on an exhibition or pop-up event.

Red Butte Garden - Botanical garden with an impressive variety of natural spaces including options for an exhibition in the main hall, orangery, rose garden theater, and other forest or meadow gardens.

Allen Park - Public park featuring fascinating ruins from an abandoned commune nestled in a forest setting, that is currently planned for renovation with unique options to build an installation and plantings among the structures in the landscape.

The Garden Store - Gardening store with a beautiful outdoor garden space featuring fountains and latticed shade structures covered in vines, with many options to set up an installation embedded into the garden.

Gilgal Gardens - Eclectic art garden with many eccentric, outsider-art sculptures playing off Mormon ideology, with open spaces for garden plantings around an installation near the entry and side sections.

International Peace Garden - Large public gardens featuring fabricated cultural landmarks from countries around the world, with a wide variety of options to create an art installation in the open fields or garden areas.

Mockup Ideas

Red Butte Garden

The Garden Store

Allen Park

Gilgal Gardens

International Peace Garden

4. Public Engagement

The final product of our collaborative project will be a pop-up exhibition with an opening event that will take place at one of our garden locations next summer. We plan to document and share our process working on this project and extensively promote it online and through social media. In conjunction with the garden installation, there would also be a public lecture at UMOCA about our process of making connections through gardening, art, and environmentalism. Conceptually, this will center around the current issues of drought and habitat loss that we are facing in Utah, and the main motivation in our work is to educate about these ideas of environmental stewardship.

This Assemblage process grant would give us the ability to go in some interesting conceptual and artistic directions that we are very excited about, and help kickstart our collaborative efforts creating collectively in a new environment. Thank you so much for reviewing our project, “The Architecture of Utopia” and we look forward to hearing from you.

"Rewilding" - Art on Main

Flower Cuttings

Portfolio

Image Samples

www.nick-pedersen.com/work-samples

Bios

Nick Pedersen (lead artist)

Nick Pedersen received his BFA in Photography from the University of Utah, and his MFA in Digital Arts from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. Pedersen's work combines his own photography, digital collage, and printmaking techniques to create elaborate, photorealistic images focusing on environmental issues. His artwork has been shown in galleries across the country and internationally, including the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art, Paradigm Gallery, Antler Gallery, and UMOCA. He has published two artist books featuring his long-term personal projects Sumeru and Ultima, and his work has been featured in publications such as Vogue, Create Magazine, Juxtapoz, and Hi-Fructose. Many of his images have been recognized with awards from the International Photography Awards, the Fine Art Photography Awards, the Adobe Design Achievement Awards, and the Photoshop Guru Award. As an educator he teaches workshops on photomontage and digital collage, and has lectured at Pratt Institute, NYU Polytechnic Institute, and the University of Utah. Pedersen has also completed artist residencies at the Banff Center in Canada, the Gullkistan Creative Residency in Iceland, the Taft-Nicholson Center in Montana, and the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art to work on his environmental projects. This past year he was awarded an arts grant for Wake the Great Salt Lake, a public art initiative through the Salt Lake Art Council and Bloomberg Philanthropy to raise awareness about the decline of the Great Salt Lake.

Amy Macintyre (collaborator)

Amy Macintyre is a garden designer and writer based in Salt Lake City, Utah. Her work blends water-wise practices with a naturalistic, dynamic aesthetic, creating spaces that are both beautiful and ecologically resilient. With a BA in journalism and professional writing from The College of New Jersey and advanced storytelling training from the UC Berkeley Advanced Media Institute, she brings a strong narrative voice to her design practice.

Before pursuing garden design, she worked as a science and medicine journalist—a background that informs her ability to communicate the profound connections between small, everyday choices and the health of our broader ecosystems. She is a Master Gardener through Utah State University and holds a Permaculture Design Certificate from USU in partnership with the Permaculture Institute. Her projects reflect a commitment to reimagining how we utilize outdoor spaces in a changing climate, merging environmental stewardship with artistic vision.